Why do we love movies so much? What is it that engages our minds so much? And why do we like, engage and excite some movies more than others? Why do we feel terror when we see the two little girls at the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, or despair when Frodo loses Sauron’s ring? The explanation could be provided by so-called mirror neurons, the latest frontier in neuroscience. Here is what they are, why they exist and how they make our existence intense.

“This Film Is About Me.”

Cinema offers such a high and multifaceted variety of plots and characters, that sooner or later it happens to everyone to find the movie they identify with. “This movie seems to be about me” or “this movie seems to be made for me” is what we would say in such situations.

And in a sense, that is exactly what happens. In the intimacy of our consciousness, it is as if the mind resonates with the moods and events of the people it sees. When we watch a feature film, a kind of magic occurs in which illusion and simulation merge but generate feelings that we perceive as real: fear, despondency, love, anguish and even a sense of urgency. It is that suspension of disbelief that persuades the viewer to suspend his or her critical faculties for the purpose of ignoring inconsistencies and enjoying a work of fantasy.

We all know that there are no Muggles or wizards, but that did not stop Harry Potter from becoming a worldwide success. How then does neuroscience explain this mechanism?

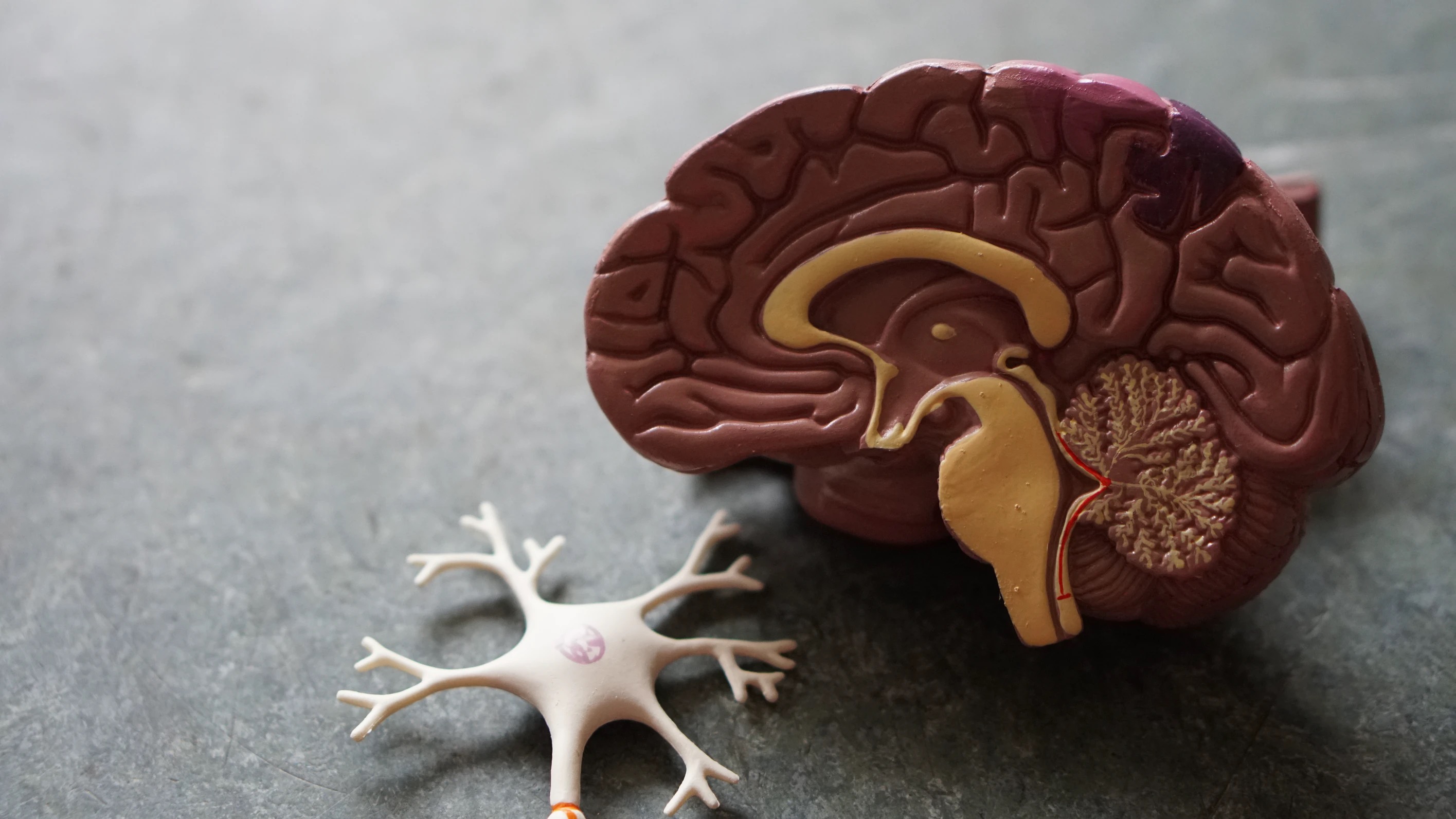

“We participate emotionally in what happens in the movies, we empathize, we are moved,” Prof. Giulio Maira explained to ANSA just a few years ago. “This happens because we have mirror neurons, neurons that are activated when we see an actor making a gesture, performing an action, getting emotional. If an actor gets excited I activate the same brain neurons, the same neural networks.”

“When we go to the cinema we are also free of thoughts, our brain is totally available to enter the reality of cinema but not passively but with an active participation: the activation of the same neurons that the actor is using-he continues-the activity of artists must be to involve the audience, but there is a physiological, neurophysiological basis in this involvement.”

Empathy and Immersion

Human beings are endowed with a capacity that is very rare in nature, namely, empathy, the ability to understand others and their state of mind. This not only makes him unique, but also gives him the ability to enjoy the representation of reality; that is, to be passionate about acting and simulation, and to derive benefit, teaching or pleasure from it.

But there is a biological and evolutionary reason for this innate ability, and a group of neuroscientists provided it in 1992. Indeed, in that year they discovered the existence of particular types of neurons, so-called mirror neurons, which are activated both when an individual performs an action, and when the individual observes or hears a particular action performed by someone else

These motor neurons, firing up even only during the observation of a certain movement (such as a jump, a greeting or a smile), activate in our brains a simulation of that act: that is, we perceive–almost as if we were doing it ourselves–the jump, the greeting or the smile. Or at least our mental representation of such actions.

The mirror mechanism, explains neuroscientist Vittorio Gallese, suggests that you can feel what others are feeling or what an actor is doing because the same thing is happening inside you. “We are in a restaurant,” he explains by way of example. “And someone reaches for the salt. The classic idea of previous cognitive theories is that I intuit that you want to reach for the salt-and that’s the ‘mind reading’ explanation. But there is a much faster way to explain that you need salt. I perceive myself-that is, my mirror neurons fire like yours-and I anticipate your actions through my body.”

We connect to other human beings because our brains replicate their moods and create representations of what they are doing. If someone is lifting a heavy suitcase, somehow you are doing it too, albeit without any real movement, and you can almost feel the load. It’s the same reason why, when Brad Pitt takes a punch in the stomach in Fight Club, you hold your stomach for the echo of the pain you experience.

Mirror neurons allow us to share our emotions, and sense those of others. But why did we develop them over millions of years of evolution?

Mirror Neurons

If you see someone extending their hand toward some food, you immediately intuit their intentions because you have made that gesture yourself a million times before. It’s kind of like the brain asking itself, “I see that you are bringing your hand toward the plate: if it were me making this movement, why would I do it?” And that gives us a profound key to understanding what is happening in reality around us.

When in Hitchcock’s Notorius, Ingrid Bergman (in the film, Alicia) reaches out her hand to steal the cellar keys, in your mind you too are performing the same action.

The suspense you feel is real because it is yours.

According to the most modern theories, mirror neurons are fundamental to human language, giving us a competitive advantage over other species because they allow us to intuit a predator’s intentions well before the action takes place-an intuition that can mean the difference between life and death.

And it is the same mechanism that probably explains why an infant can reproduce movements of its mother’s mouth and face within hours of birth. And if you give it a tongue, it responds in the same way: because it is something innate within each of us.

Mirror Neurons and Cinema

Is this enough to explain the emotional involvement one feels at the movies? Not really. The predisposition is there, but then a lot also depends on the technique used by the director, the cinematography, the music and so on: it is the combination of these elements that makes us immerse ourselves in the action. More in detail:

- Machine Movements: Neuroscientists have asked, “what happens and how does perception change in viewers if you change key elements such as camera movement, given the same scene? Between static image, zooming in on the actor, forward tracking or steadycam (camera worn by the operator who is free to move)? The result was surprising: the use of steadycam activates the mirror neuron mechanism much more than the others. It is as if we are there in front of the scene, unseen (think of the camera following the child on the tricycle in The Shining, generating anxiety for the viewer).

- Zoom: Immersion is useful to create suspense, anguish, but sometimes the director wants to achieve just the opposite, namely detachment and estrangement of the viewer. In this sense, zooming in is perfect because it shows us scenes as if they were so many paintings, reducing their emotional component. This is because zooming is not a type of movement that the eye can do naturally. Just think of the effect seen in Revenant or in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon.

- Classic Editing: In the end, the films that most activate mirror neurons are those that are classically edited, which partly explains why some Hollywood titles have become blockbusters. But classical editing doesn’t mean that you can’t play with viewers’ expectations and raise the level of tension. An example? In Silence of the Lambs, at the end it looks like half the FBI is in front of the killer’s house; instead, the only one present is Jodie Foster.

Mirror neurons, in short, do not explain everything, but they help us better understand the origin of the wonder that is cinema for us, a subtle middle ground between the “fiction of the real, and the reality of fiction.”